It’s round, it bounces, it’s called the Brazuca: introducing the new World Cup football

Stuff looks at five reasons why Brazil 2014’s weapon of choice is “the most tested football ever”

You don’t have to be a die-hard season ticket holder with a full back tattoo of your favourite team to know that balls are rather important in Football.

Adidas – official provider of the World Cup ball – seem to take the art of creating kickable spheres rather seriously, as we’re about ot find out…

The proof is in the panels

The most revolutionary technology in the Brazuca is its unique outer shell. Six crosses of identical, if not entirely uniform, design connect together to form a thermally bonded case to make the ball as consistent and accurate as possible.

“They lock together into a harmonic design,” says football innovation director Antonio Zea. “It’s a simple, but beautiful, product that we hope players will love to use, their lucky ball.”

Throw in pimples that maximise foot-to-ball contact that have been a major part of the current Champions League football – the base for the Brazuca – and it’s an impressive bit of kit.

Water absorption (or lack thereof)

For any football to be used in an official match, it must pass a series of FIFA criteria governing its weight, roundness, how it bounces at 20C and 5C, water absorption and durability.

“Whatever the FIFA standard tests, we wanted to better them,” says Mecking. “For example, the Brazuca only gains 0.2 per cent of his weight in wet conditions, so it performs equally well in all conditions.

The FIFA standard is 10 per cent.” The ball sits inside a machine in 2cm of water and oscillates 300 times, its weight compared to the reading at the beginning of the test.

The aerodynamics of progress

Usually the preserve of fighter jets and the odd super car, Adidas have measured the Brazuca’s aerodynamic capabilities. “It’s slightly more theoretical than some other lab tests,” says Matthias Mecking, business unit director for football hardware, “but is still a very important way of assessing the Brazuca’s flight path behaviour.

The Reynolds tests works out when the ball leaves the ideal flight curve, the Yaw test measures the ball’s in-flight movement and the Reverse Magnus effect tests how it reacts to swerve and when it deviates from the ideal path.” All that, just for football.

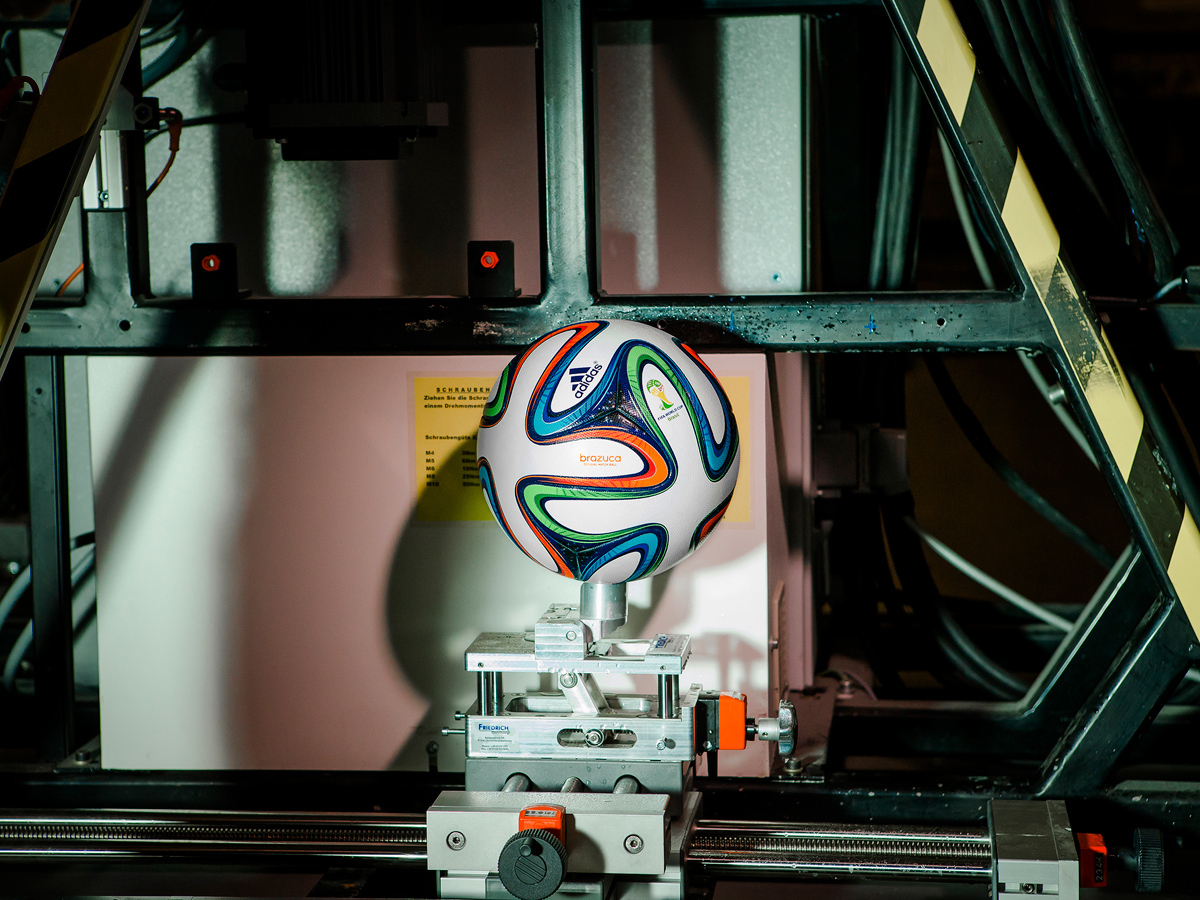

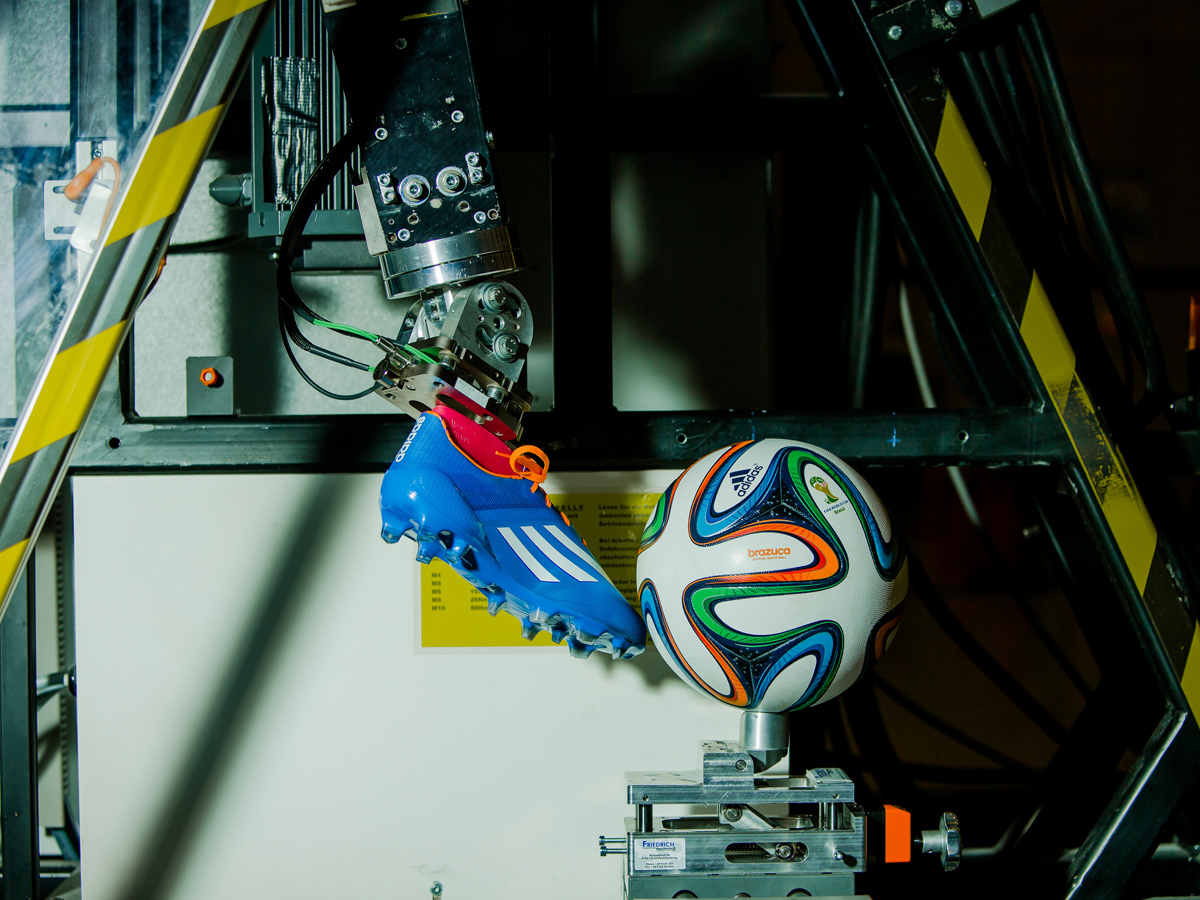

Who needs players when you’ve got robots?

After the lab comes what the Adidas boffins call ‘objective testing’. At the centre of the Adidas Innovation Team (AIT) lab is a robotic leg that simulates kick after kick for a frame-by-frame camera to assess minute deviations that could only come from a problem with the ball.

“We needed repeatable, scientific results,” says football innovation director Antonio Zea. “The robot leg allows us to kick a ball the same way every time. We can test the flight path, accuracy and speed. We can also wet the ball and test in different conditions too and even put different boots on the end of the leg to test how that affects everything.”

Player testing

In total, the ball has been in development for two-and-a-half years, travelling to 10 countries and has been tested by more than 600 players.

It’s these subjective tests that have provided the backbone, including live tournament testing – with a disguised design – at this year’s Under-20 World Cup in Turkey for the first time ever and tests with 30 teams around the world from Chelsea and Bayern Munich to the Spain and Argentina national teams.

“It all sounds nice, in theory, but I wouldn’t be talking about it if I didn’t believe in it,” says Mecking, who has been working with the company for over 15 years. “We can truly say that the Brazuca is by far the most tested ball we’ve ever produced. We’ve never spent so much energy in testing a ball.”

So there you have it. Whatever happens at next summer’s, it won’t be for the lack of tech in the ball that causes open goals and keeper foul ups.