Why it’s time to get pumped about flexible screens

Gadgets can be stubbornly rigid, but the days of cracked screens and chunky cases will soon be over: welcome to the flexi-tech revolution

Tablet and smartphone touchscreens might seem advanced, but displays have even further to go. While we’ve been stubbing our fingers on glass, scientists have been cooking up the tech needed to make ‘flex-to-zoom’ a reality, with the billions now being pumped into graphene research a major catalyst. But why would you need a fold-up iPad? And how long before we’re reading paper-thin digital rags on the train?

The reason today’s gadgets are annoyingly rigid? Their guts are mostly made using materials that don’t bend. At all. That’s why most have a sandwich-type structure, with front and back covers and rigid components between the two.

Bendable gadgets require totally new materials and manufacturing techniques – but as you’re about to see, such materials and techniques are at a more advanced stage than you might think. Make no mistake: flexi-tech is a question of “when” rather than “if” – but before we delve into the how, what about the why?

Why make gadgets bendy in the first place?

One advantage of flexible gadgets is ruggedness. Rigid tech can snap and break, but flexi-tech, such as Samsung’s Youm display (shown off at Las Vegas’ CES show back in January), is hardier. Its engineers say the plastic, bendy Youm will not break, even if you drop it on the floor.

Flexibility can also improve user interfaces, particularly for devices like smartphones. Says Nokia’s Advanced Design head Tapani Jokinen: “Bending and twisting these devices could make interaction much more natural and intuitive”. Think “squeeze-to-answer” or “twist-to-scroll” instead of “pinch-to-zoom”.

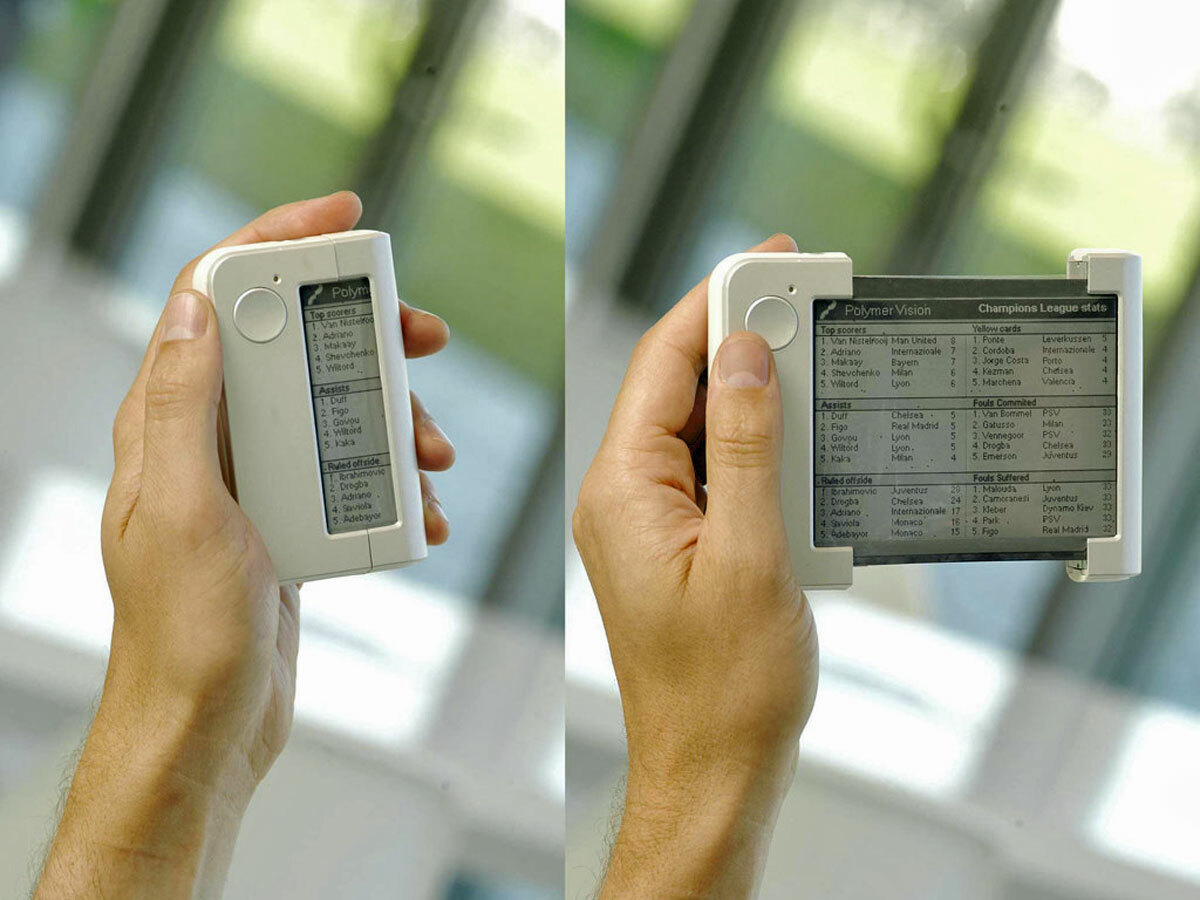

Tablets will be one of the biggest beneficiaries of flexible tech. In fact, the next-gen materials and manufacturing techniques will likely change our whole concept of what a tablet is. The first stage of flexible tablets is already underway, and will see the arrival of bendy “second screen” devices that offload processing to more powerful rigid devices. These are likely to use the E Ink tech already seen in Amazon’s Kindle devices. “There are about 30 million flexible E Ink display in the field today,” says E Ink marketing chief Sriram Peruvemba. “And in the past we’ve even created displays that will roll up into a tube just a few millimetres across.”

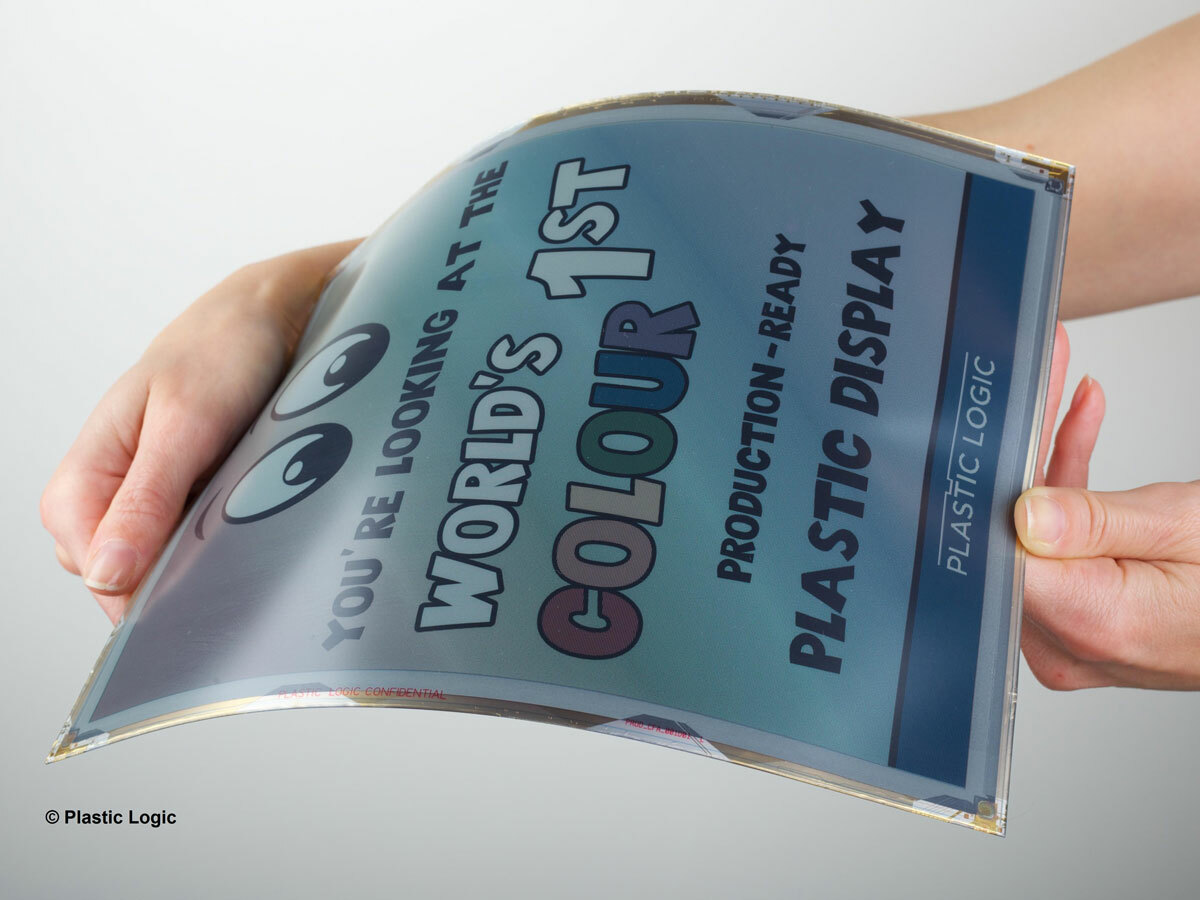

E Ink uses thin-film transistors bonded to plastic sheets to power black-and-white pixels, but colour flexible screens are on the horizon. Cambridge-based Plastic Logic is working on it: “To get colour,” says the company’s Rachel Lichten, “you have to align a filter to within 5 nanometres of each pixel on the flexible backplane. Not easy – but we can do it.”

Youm: Samsung’s curveball

Samsung’s Youm concept screen, shown off at this year’s CES conference, doesn’t use E Ink tech but full-colour OLED, and delivers rich, lush graphics while remaining flexible. Youm is beyond what is possible with today’s tech, but promises displays that can fold, bend and wrap around devices to provide extra display capacity on the sides of phones and tablets (say, to slyly read a text message during a meeting).

How soon is flex?

Plastic Logic has already developed a bendable reading device with E Ink-style technology, but it still requires unbendable components, which are squeezed into a narrow, stiff spine. But the key to fully bendable gadgets is flexible components. Miniaturisation in electronics means that a lot of components are already becoming smaller, thinner and intrinsically more bendable, and wiring and transistors are already flexible, but certain parts – namely processors – are still stubbornly rigid. Gadget manufacturers can compromise by lumping the inflexible parts together in “islands”, connected by wiring, which will allow specific areas of the device to bend.

Which brings us to the second stage of flexible devices: a new generation of foldable, if not yet rollable, tablets. You’ll remember the ill-fated Sony Tablet P, which opened along a hinge to reveal two screens. Now imagine a slimmer version with a flexible, continuous screen, perhaps with more hinges to let it fold many times.

“It could bend into plenty of other shapes: to play games with, or to type on,” explains Sriram Subramanian from Bristol University’s Interaction and Graphics department. “In the future, when you download software you won’t just download an app, you’ll also download an appropriate shape for the device.”

Progress points to foldable tablets could be in your hands by 2016.

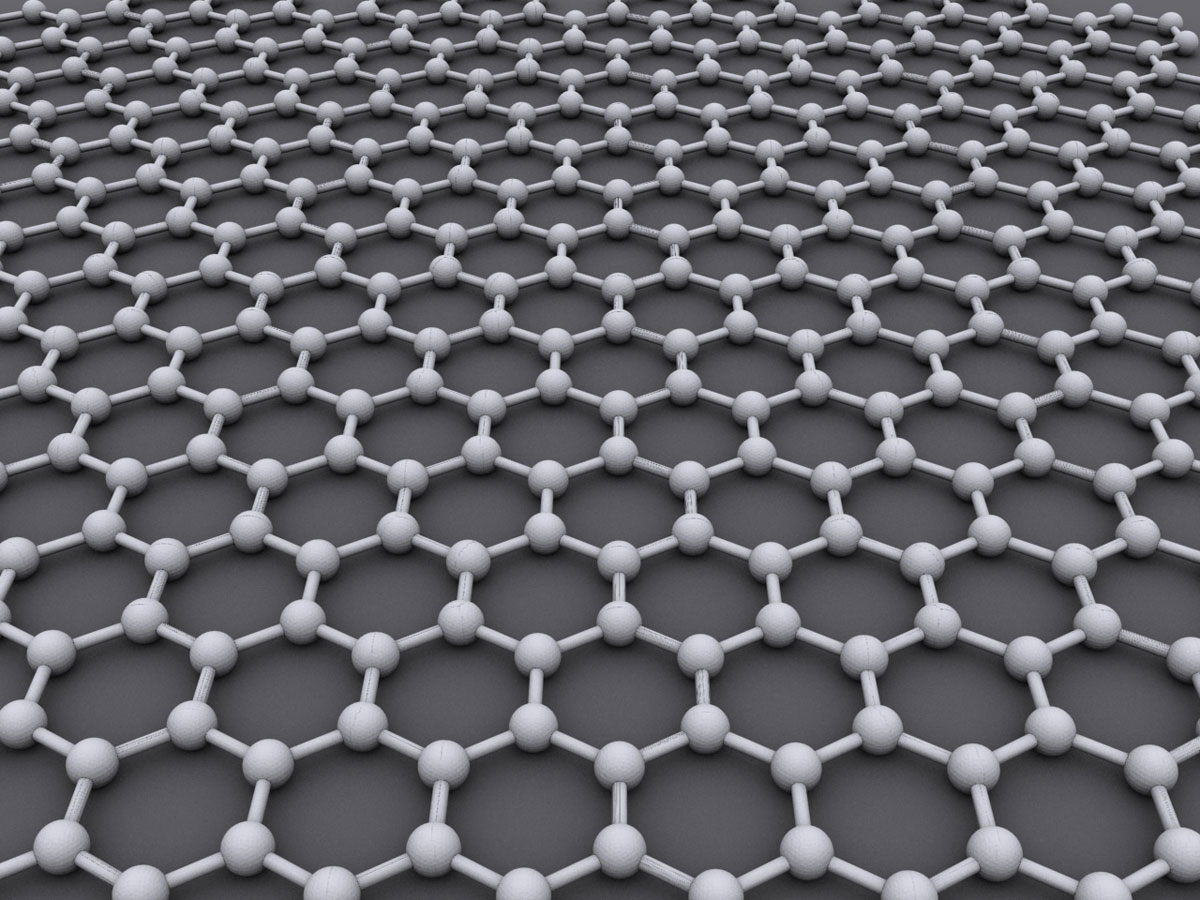

Graphene: the wonder material

Flexi-tech’s exciting possibilities lie in a revolutionary material called graphene. Super strong and incredibly thin, graphene will allow engineers to make incredibly light, flexible components that are practically indestructible – and perfect for use in bendy new gadgets. Thanks to the European Commission’s injection of €1 billion towards the development of the super-material in January 2013, graphene is finally ready to take gadgetry’s centre stage.

Folding is all well and good – but what’s the third stage?

The holy grail of flexible tablets is a fully rollable tablet whose every component bends to your will. But it requires further advances: the processors that currently drive your tablet are built on hard silicon wafers, so scientists are working out how to create processors from different materials. Or, more likely, remove the number-crunching circuits from their wafer-bound existence and place them on to rubbery, stretchable bases.

“Because of their thin dimensions, once they’re off that wafer, they’re inherently flexible,” explains materials scientist Professor John Rogers. The good news is that it’s possible; the bad news is that it’s likely to be 2020 before they’re fast enough to power a respectable device. It’s a similar tale for the rate of progress with memory, too. Batteries? They’re an even bigger problem because their capacity is dictated by volume: make them thin enough to be flexible and they barely hold any juice.

Instead, researchers believe devices will need more than one power source. “For that reason, we’re looking at wireless power,” concludes Rogers. That amounts to pumping energy into devices through the air via radio waves, relying on the science of magnets to harness power in the device.

The future is bright – and bendy

The future of tech is most certainly bent, and we’re already seeing the first signs of this pliability. Bendable screens are now a reality, but the inflexibility of gadget innards means those from the likes of Plastic Logic will initially act as secondary displays in the form of e-readers and watches. These will be quickly followed by folding, book-style tablets, which will use the OLED tech shown recently by Samsung Youm. But it’s the European Commission-powered acceleration of graphene that holds the key to true roll-up tablets. If all goes well, by the end of the decade we can expect it to produce wafer-thin, colour-display tablets that you’ll be able to pocket – if you can bring yourself to stop using them, that is.

Words by Jamie Condliffe