Project Ara: how Google set out to build the last smartphone

Tired of upgrading your phone every few years? Meet the modular chameleon that might just be the only portable gadget you’ll ever need…

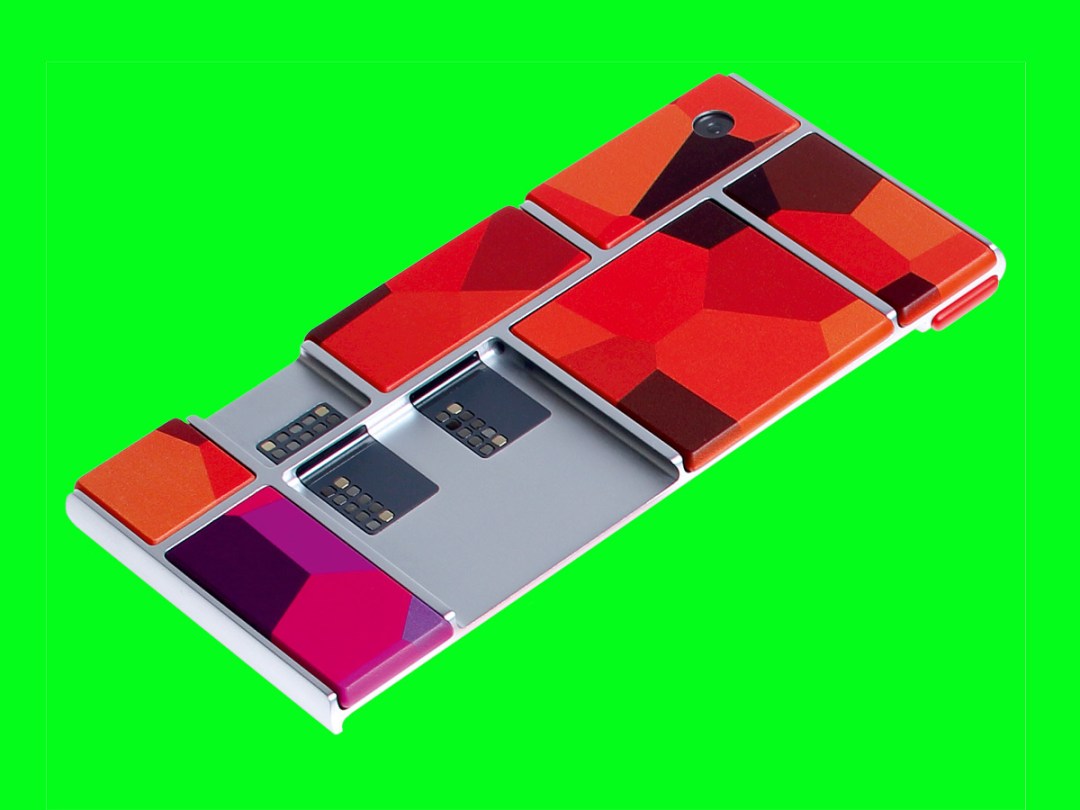

In the future, your phone won’t be a single chunk of gadgetry.

It’ll be a collection of things that you can click together into phones of different sizes depending on how you’re feeling, what you’re wearing and what you plan to do. It’ll have every sensor under the sun, but only if you decide to add them, and it’ll be permanently future-proof, because adding a new processor will be as simple as slotting in a SIM card.

Sounds like a fairy tale, doesn’t it? But it’s happening. Very soon in fact. Google’s Project Ara aims to usher in a brave new world of modular smartphones, with the sales of the first generation of handsets due in Puerta Rico later this year.

Join us as we travel into the brave new world of Project Ara to find out if it really is the last phone you’ll ever buy.

READ MORE: Living with… the Google Nexus 6

A phone you can break

How many gadgets have you bought? As a Stuff-reading technology wizard, we’re guessing your answer will be: “Oh, most of them.” But how many of them have eventually stopped working and been thrown away? Sadly, your answer is likely to be the same: most of them.

For decades we’ve bought things we can’t repair, with screens that break and batteries that lose their juice after six months. And every time that happens, we check our insurance, summon a shiny new replacement and send the old gadget to be buried in a mountain of VHS tapes, broken furniture and those bags of salad that never get finished. There has to be a better way.

It was exactly these kinds of thoughts that began bouncing around the brain of Dutch product designer Dave Hakkens last year when his camera broke. Or rather, when part of it broke. That part was easily replaceable – although he’s not an engineer, Hakkens was able to spot the defective lens motor and remove it. The only problem was, he couldn’t get a replacement, because camera companies don’t sell lens motors. They sell cameras.

“That’s the weird thing about electronics,” says Hakkens. “If your car or your bike is faulty, you fix it. But with the camera, they said I should just throw it away and buy a new one.”

Instead, Hakkens began thinking about how to make gadgets that could be repaired and upgraded, rather than replaced. He quickly realised the ubiquitous smartphone was the best place to start, and began designing a phone with removable components that could be swapped when they break or get old.

But while Hakkens has a gift for ideas, he’s not an electrical engineer. “I had an idea for a phone, but I couldn’t build it,” he says. “So I thought, what’s the best way to get this done?”

The answer was to do what no large company in its right mind would do with an idea like this: he made a video explaining his idea, and put it on the internet.

The response to Hakkens’ concept phone, which he called Phonebloks, was huge. Within days he had over 900,000 supporters on the Thunderclap public speaking platform and the campaign reached an estimated 380 million people on social media, not to mention TV, newspapers and magazines (yes, you did see it in Stuff magazine’s Hot Stuff section).

Among the huge number of responses, there was an email that would make Hakkens’ dream a reality.

“We got a lot of people and companies responding, and one of them was Motorola. They said they were working on something similar, but they’d been doing it secretly in their lab.”

ENTER ATAP

One of the people who had been hard at work in that secret lab was another designer, Gadi Amit. Gadi’s own company, New Deal Design, has shaped a significant portion of the tech that’s graced our website in the last few years, including the FitBit, the Lytro camera, the Airocide air purifier and designs for Dell and Netgear.

Gadi’s team was recruited by ATAP, the secretive Advanced Technology And Projects group within Motorola (and then Google following its buyout of Motorola in 2012) that cooks up futuristic technologies in unmarked buildings on Californian business parks. ATAP describes itself as ‘a small band of pirates’, which is exactly the kind of thing nerds like to call themselves, and has the motto ‘We like epic shit’, which sounds confusing and disgusting but apparently means something quite different in American.

ATAP’s brief is to pick wildly ambitious goals and deliver them in two years. The brief they gave Gadi’s team was unlike anything they’d been asked to do before.

“They said they wanted a modular phone that could serve six billion people,” explains Gadi. “They wanted it to have a malleable configuration, a high-technology core that can work with low-cost, detachable parts, and they wanted people to be able to 3D-print elements of it.

“We came up with around 10 kinds of phone. We had a design that looked like a normal phone, but you would ‘pop the hood’ at the back and inside you’d see a variety of components attached with flat cables or connectors, very much like a PC. The problem with that concept was that if someone like my mum wants to swap a component… well, she probably won’t do that, because she’s not the sort of person who opens a PC to replace the RAM. So this concept would appeal to tech enthusiasts, but it’s not for six billion phones. Then we looked at a hybrid model – half the phone was closed, and then half of it had interchangeable modules that were visible from the outside.

“We looked at phones that came in layers, like a cake, layer on layer on layer. And we had a concept that was similar to Phonebloks in the sense that there wasn’t a skeleton, only blocks that connected to each other, which we called the ‘Lego phone’.

“Both of these had a fundamental problem, though, which was that if you want to make the platform reliable, you have to be able to control the core communication bus between the different components. You don’t want to have one component communicating with another by way of the component in-between, because if the component in the middle is slower, it’ll limit the performance of the whole phone.”

“So we kept trying new ideas, but the concept that was a winner every time was the idea of a phone with a rigid grid of modules of three sizes that slotted into an inner skeleton. It’s just like having a spine and a central nervous system, and that’s why we used the word ‘endoskeleton’, in a biological sense.”

But Project Ara’s endoskeleton isn’t just a dumb connector. “You can swap out a battery,” says Gadi, “while you’re making a call. The endoskeleton will maintain the call for up to five minutes because it has its own internal battery.”

How to buy an Ara phone

Magnets from the future

When Dave Hakkens visited Google for his first look at Project Ara, his favourite part of the design was the way the modules are held in place. “My design had a board with modules held in by pins, but Google is using electropermanent magnets, which are quite a magical thing. It’s like an electromagnet, only usually an electromagnet always requires current. This one doesn’t – you can flip the polarity to turn it ‘on’ or ‘off’, but while it’s on or off it’s not using any current. And when it’s stuck, it’s stuck.

“So to release the modules, you have to tell Android to release them and it’ll switch the magnets off, but while they’re on, they won’t fall out and you can’t pull them off – it really feels like a solid phone. It’s a really nice, futuristic piece of technology.”

The skeletons themselves come in three sizes: a small ‘candy bar’ format that Gadi Amit says was chosen for its ‘pocketability’; a standard smartphone size; and a phablet. Because swapping modules takes seconds, this means if you own all three you can change the size of your phone (but keep using the same memory, processor, camera and so on) depending on what you’re doing. And as far as extras are concerned, the possibilities for modules are almost endless.

“It’s like an app store, basically,” says Dave Hakkens. “I’ve heard some good ideas for solar modules, to add solar charging. One of my favourites came from a woman who has diabetes, who responded to our video saying you could have a glucose meter block, so she could measure the amount of sugar in her blood. I would never have thought of it myself, and I don’t think any phone maker would ever have come up with an idea like that, but if you think about it there’s a really big group of people who would want that in their phone.”

But what Hakkens says he’d like to see is more established companies lending their expertise to modular phones. He’s currently working with Sennheiser on audio blocks, such as DAC modules for audiophile-quality headphone sound or better built-in speakers, but he’s eager to get other firms to bring their expertise in making cameras, batteries, processors and anything else you care to imagine into modular phones.

And he’s particularly keen to get chip manufacturers involved (Qualcomm, not McCain… although some sort of tiny deep-fryer module could be handy for mid-call snacking). If you can replace the processor each time Nvidia or Intel brings out a newer, more powerful system-on-chip, the old processor can be easily recycled, the upgrade process takes place piece-by-piece, and your phone is always the most powerful phone you can buy.

How to change an Ara module

Upgrade everything

So how and when can you get hold of an Ara? Unless you happen to be in Puerto Rico right now, it’s hard to know. The United States island territory is where Google plans to initially release the Ara in a ‘limited market pilot’ sometime during 2015. Details and dates of this pilot are still relatively unknown and Google is yet to comment on when this product will be rolled out across the rest of the world. So for most of us, it’ll simply be a matter of waiting (and wishing that everything goes to plan).

If Project Ara goes down a storm then it could pave the way for a completely new breed of customisable gadgets. Module bays will become as commonplace as USB ports. You’ll be able to add processors and sensors to TVs, coffee machines, cars and anything else to which you can legally take a soldering iron. You’ll be able to upgrade everything you own, without throwing anything away.

All of which has to be good for the planet, good for the tech-obsessed and, ultimately, good for our wallets.