How technology is killing the ticket tout

Ticket touts are the cockroaches of the music world, but tech is making it easier to stomp on them...

Sometimes getting tickets for a gig seems harder than just learning to play all the instruments and getting up on stage yourself.

Part of the problem is that buying tickets isn’t a level playing field. Touts use bots that automatically buy tickets faster than a human can, a bit like those plug-ins that bid on eBay listings for you at the very last second.

Once an event has sold out (and sometimes even before) those tickets often gain in perceived value quicker than a one-bed flat in the outer orbit of London, and in an age where social media has made FOMO practically treatable on the NHS, some people will always vote with their soon-to-be-very-empty wallets.

Ticketmaster (more on them later) claims to be spending more than anyone else in the industry to fight bots, with thousands of attempted illegal transactions blocked every day.

“Our IT teams continually analyse traffic patterns and are able to block bots based on the non-human nature of the patterns they use,” a Ticketmaster statement said.

“A key and successful initiative is the software that we employ to identify multiple purchases from the same IP Address. Once identified, we then block these IP addresses and share them amongst our global networks to ensure that they cannot repeat activity anywhere in the world.”

But clearly it’s not quite working.

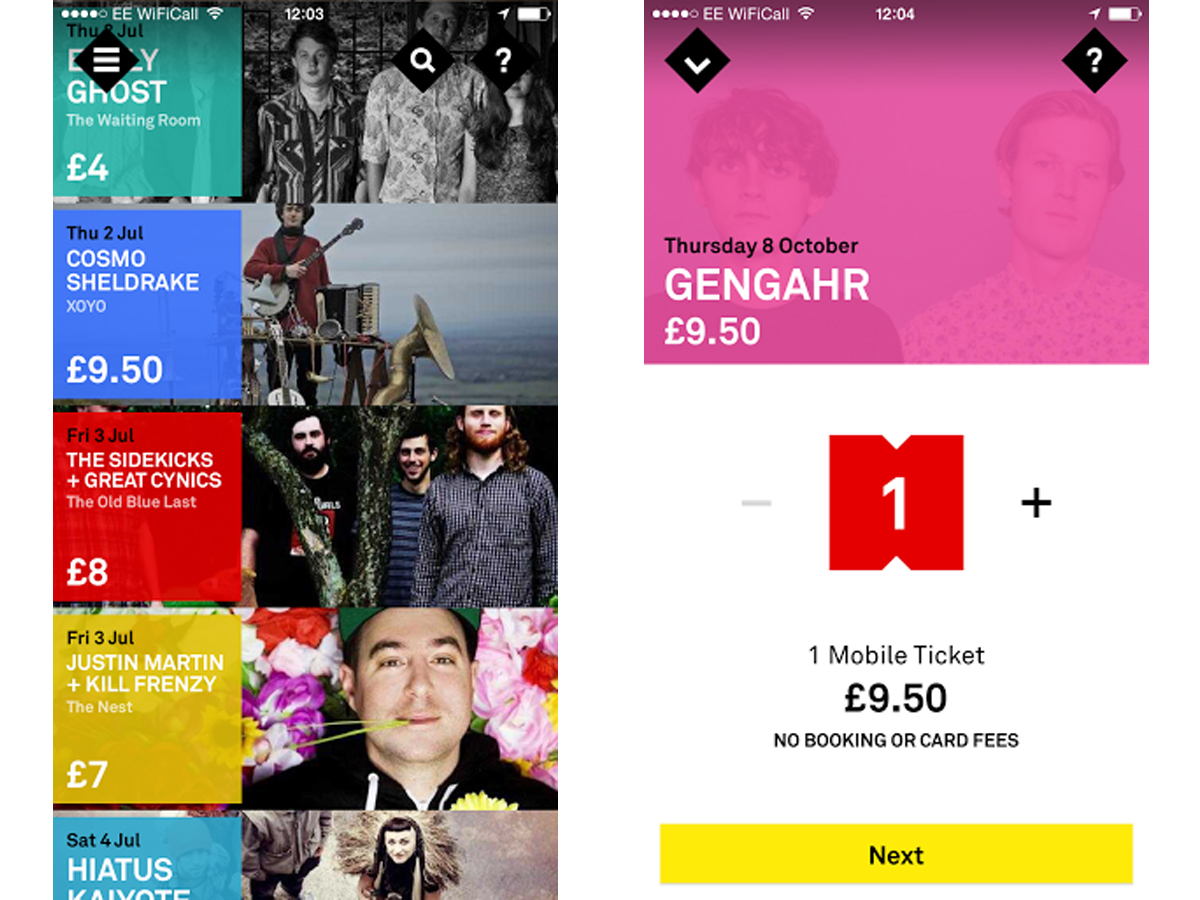

Roll the dice

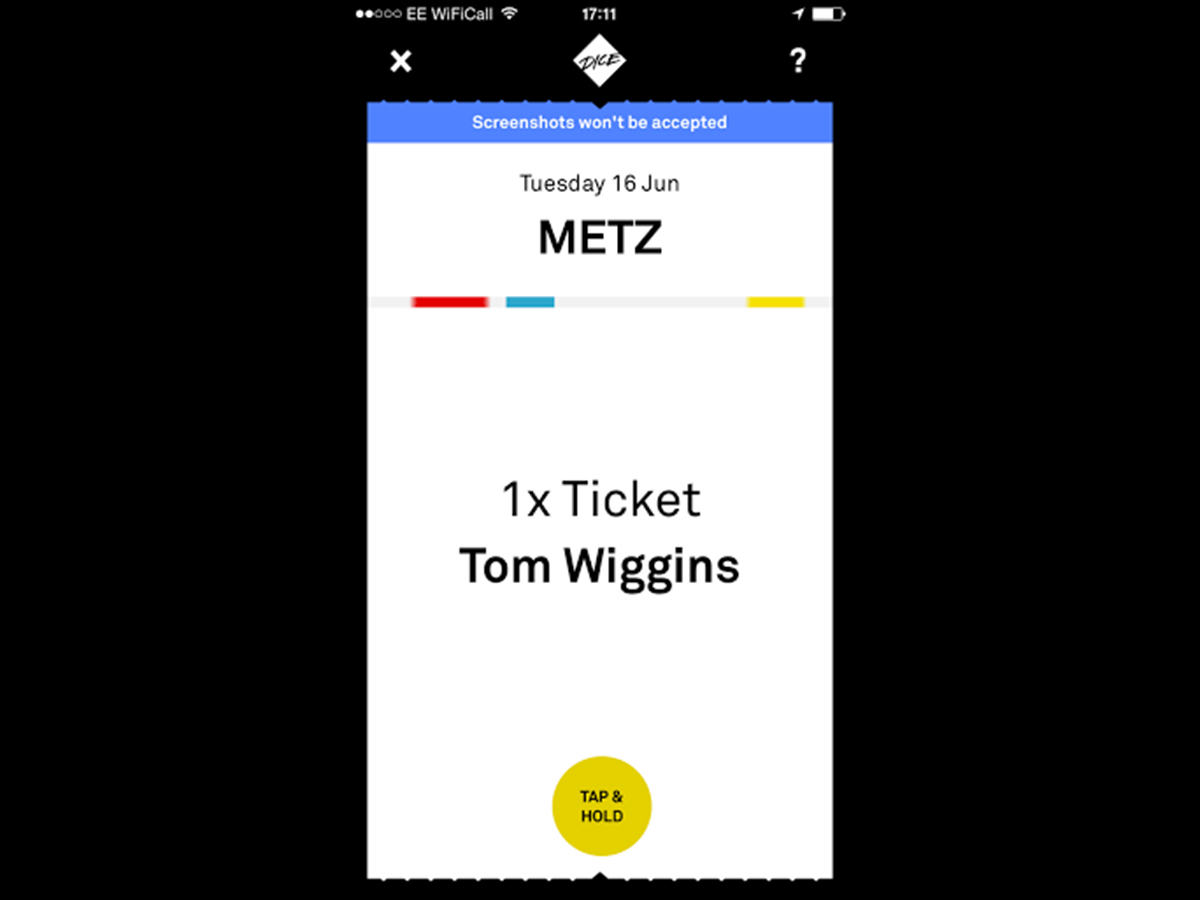

Dice is mobile only. Go to the website and it’ll direct you towards its app in order to buy a ticket, which might be more convenient, but also means you can’t sell your ticket on. Well, you could, but it’d mean selling your phone with it – and that’s probably a step too far for even the most cash-greedy tout.

But how does it stop the bots? “You stop bots by being 100% mobile,” Dice founder Phil Hutcheon tells Stuff. “It stops them from bypassing Captcha codes and harvesting up tickets because they’re attached to the fan’s phone.”

So why not just take a screengrab and sell that? Dice has taken a leaf out of Snapchat’s book and a warning will pop up if you take a screengrab of a ticket to say it won’t be accepted, plus the ticket page is animated, so showing a static screen on the door will result in nothing more than a sad, early walk home.

If a show sells out, the app will let you return your ticket to be sold to someone on the waiting list and your money will be refunded, but if Dice still has some of its allocation left and you can find someone to sell your ticket to, you can get its customer support team to transfer it, although in that situation it’s down to you to sort out the financial side of the transaction.

That’s potentially problematic because it takes the money outside of Dice’s system, although the fact that a human being from its customer support team has to be involved should mean any suspicious behaviour can easily be spotted.

A Mist opportunity

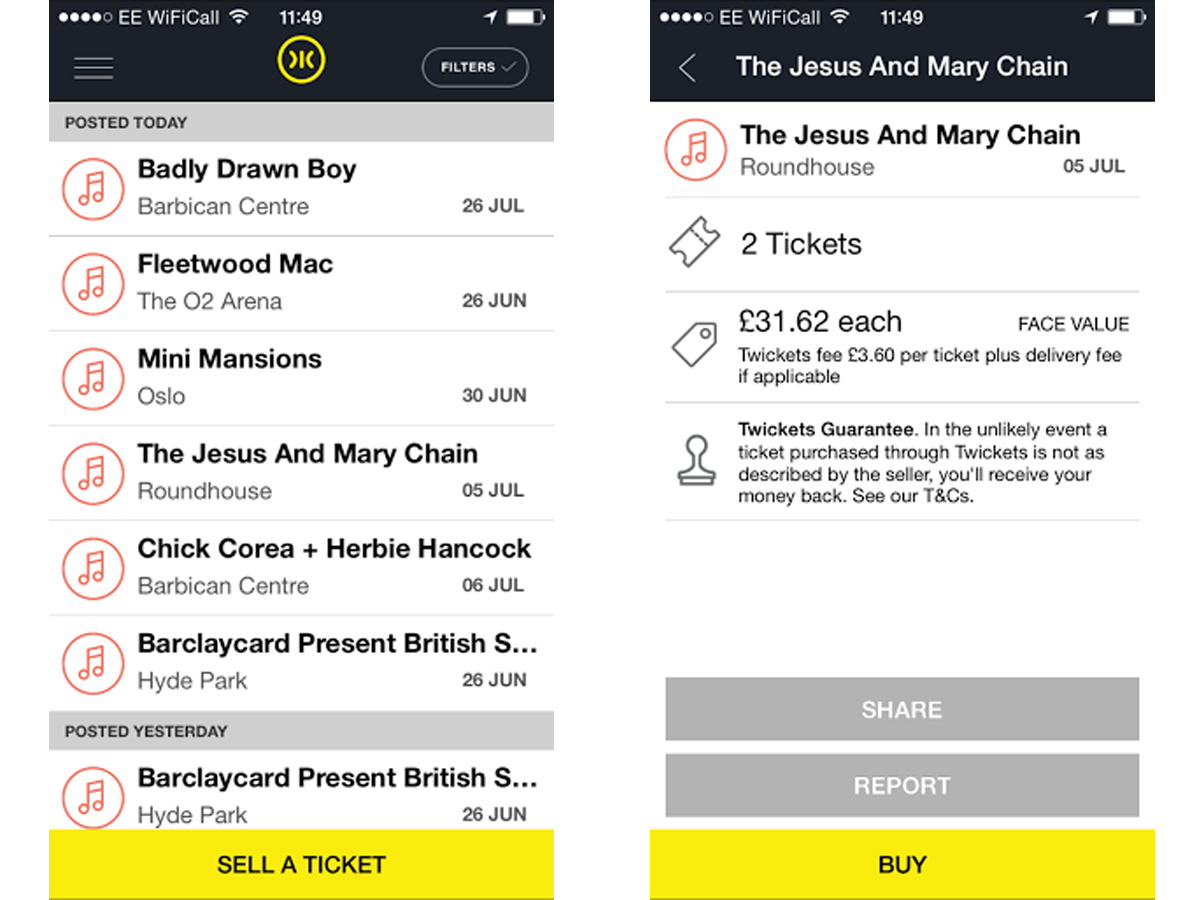

And that’s where Twickets comes in. While it won’t allow you to sell a ticket bought from Dice, and selling paperless or ID-controlled tickets is potentially a pain, Twickets is the fairest, most developed system for selling unwanted tickets ethically that Stuff has encountered since the demise of Scarlet Mist (RIP).

Launched in 2013, Twickets started as a Twitter account to aggregate spares for sale, with a strict ‘face value or less’ policy that ensured touts couldn’t use it to rip people off. It was very much driven by the community and has since developed into an efficient, well-organised marketplace for shifting second-hand tickets, with around 300,000 users across the UK, and apps available for iOS, Android and even Windows Phone.

Users can either post tickets via recorded delivery, use a new drop and collect service, or, as is most popular, meet up in person to make the exchange.

“We like that because it reinforces the community aspect,” says founder Richard Davies. “It fits well with the whole mantra of Twickets. People should be trusted to work in that way and 99% of the time they do. We see very, very little fraud, and very little overpricing. As a delivery mechanism it’s something we’ll always want to support.”

A pizza the action

Of course that doesn’t mean there’s not technology in place to back them up. Davies has experience building mobile payment systems for companies such as Domino’s Pizza, so Twickets’ team of moderators have tech that helps them to sniff out people who might be abusing the service, or trying to sell overpriced or counterfeit tickets.

They look for ‘tout-like’ behaviour, which doesn’t mean middle-aged men standing outside a tube station dressed like a casualty of Britpop and chain-smoking roll-ups, but rather somebody who’s buying up an unusual amount of tickets.

“Someone who’s buying very regularly can usually only mean one thing: that they’re looking to resell,” explains Davies. “If we suspect someone then we’ll flag them, and if that continues we can ban them from using the service. We monitor quite closely who is buying and selling from us.”

Of course, touts could use Twickets to sell spares, but with the restrictions on price it wouldn’t be worth their while. “I think what Twickets is doing is a great thing for fans,” says Dice’s music editor Jen Long. “You should be able to pass your ticket on, just not at the detriment of a fan who’s really desperate to go to a show.”

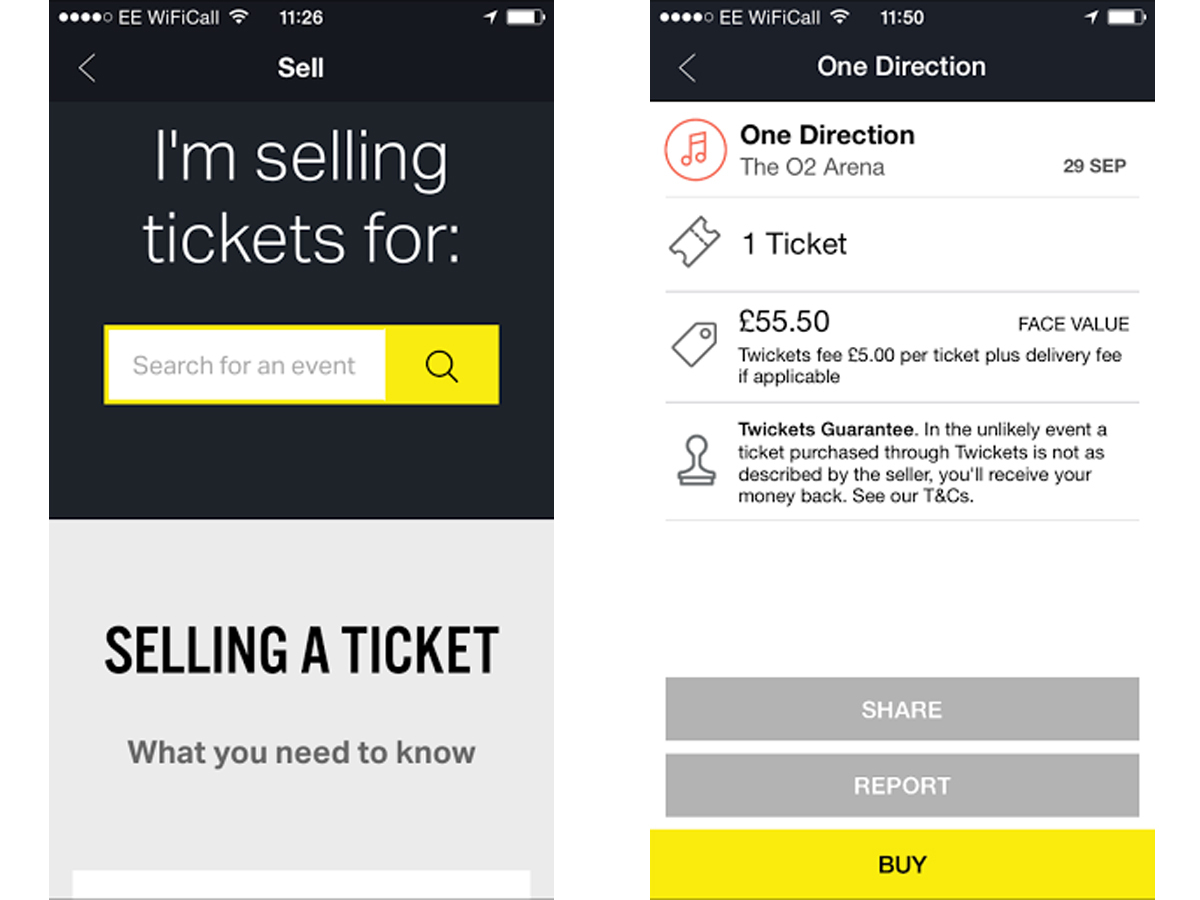

An oyster card for gigs

So where’s the middle ground? It could be Una Tickets, a soon-to-launch service that potentially provides all of the above in one place. Una has an app for iOS, Android and Windows Phone with similar anti-touting tech to Dice, but users who sign up also get a physical Una Pass, complete with a picture of its owner on the outside and an Oyster-style NFC chip on the inside, for a one-off fee of £5.99 (although they’re free now if you hurry).

“The advantage of that is there’s no touting or counterfeiting because there’s no actual ticket stored on the pass, it’s stored on your account,” co-founder Amar Chauhan tells Stuff at Brighton’s Great Escape festival.

And if you can’t go? “We allow consumers to resell their ticket, or transfer them to friends and family. The marketplace is limited to face value or less, so it’s a last resort really.”

Regulators, mount up

But there’s a balance to be struck. “It’s admirable that organisations and event owners are putting in measures to stop touting but you’ve got to be careful not to upset and disrupt genuine fans who want to sell tickets for reasons beyond their control,” argues Davies.

“Some people can’t make events and tickets go on-sale increasingly far in advance of the date itself. In that period you might find your plans just change, so you want to trade that ticket.”

And that’s the crux of the issue. It’s about regulation, not prohibition. This isn’t about stopping somebody from selling a pair of tickets they can no longer use to someone who missed out the first time, it’s about stopping the rip-offs that occur every single day – and it goes far deeper than the geezer outside the venue hawking a pocketful of spares.

Tout and about

Ticketmaster owns two reselling sites: GetMeIn and Seatwave. It argues that doing so brings the secondary market into the open, but both of those sites frequently see tickets for sale at many times their face value. Ticketmaster’s fight against bots is an attempt to maintain a level playing field, but its attitude to reselling leaves the system open to abuse by people looking to make a quick buck.

Challenge the owners about this and they’ll say that the sellers set the prices, not them, and that “trying to restrict the open market wouldn’t work and would be unenforceable,” but other countries in Europe, such as Belgium and Denmark, already cap the profits people can make from selling second-hand tickets.

Chauhan takes it a step further: “Ticketmaster is the world’s largest tout, so why would they get rid of it?” he says. That sounds shocking, but comes as no huge surprise when you consider the company was sued by Bruce Springsteen in 2009 for directing fans towards vastly inflated tickets on TicketsNow.com (its GetMeIn equivalent in the US) when tickets were still available at face value from its standard website.

“The abuse of our fans and our trust by Ticketmaster has made us as furious as it has made many of you,” Springsteen said, leading to an apology from Ticketmaster, refunds for the affected fans and more proof that you don’t mess with The Boss.

Measure for measure

Measures are being taken, with an amendment to the consumer rights bill in the pipeline to increase transparency, but Davies doesn’t think it takes things far enough. “Greater transparency around sellers would highlight the prolific nature of the selling that goes on on these platforms,” he says. “These aren’t individuals, they’re operations. They’re companies trading tickets in large volumes to fans, but posing as other fans. That, for me, is what’s wrong.”

If Ticketmaster et al are right and the market really does decide, it’s hard to see it choosing the hyperinflated prices of GetMeIn and StubHub over any more ethical alternative, but as more people are made aware that there are other options hopefully we’ll start to see a shift.

Festivals such as Kendal Calling and Secret Garden Party have already chosen Twickets as an official reseller for second-hand tickets, and according to Chauhan, Una Tickets is “speaking to major promoters and festival organisers” in preparation for its full launch in August.

Ticket touting isn’t simply selling a rightly owned commodity like a car or a delicious sandwich (both of which would lose value the instant you bought them new); it’s selling access to art at exploitative cost, making money off the fans that the artist will never see.

And when very few of them make any from selling records anymore, that’s a problem for everyone.

Update 30/6/2015: This article has been updated to correct an inaccuracy in the reporting of Dice’s ticket transfer policy.

Related › Tidal review